1: Lisboa I’m sorry

So rituals are to time what objects are to space, says Saint-Exupéry and Byung-Chul Han. They make a place habitable; temporal techniques of making oneself at home in the world.

These waters shock my reservoirs, an aqualogical micropolitics and I’m teeming; lost in an endlessly reconfiguring Airbnb of modern tragedies, mangle realism.

These dosa chips culture. This avocado, sourdough, micro greens, eggs sous vide; a desk or a life preserver, for chronos.

This phone knows me more than it’s letting on and leads me down an alley to a project space for an art book publisher.

A young man from Italy lets me in and shows me around. There’s a small talkative bird and a quiet colleague at a desk.

The space is brutalist, concrete, with open stairs and wooden shelving stacked in dense lattice.

I ask him about his work and he shows me beautiful pictures, after Luigi Ghirri, that communicate his sensitivity to light and nuance.

Fading church spires and the rhyming ornamentation of an upturned industrial plastic bottle container. Another of those standardized forms of interlocking orthogonal transport, ensuring its bad decisions are evenly distributed.

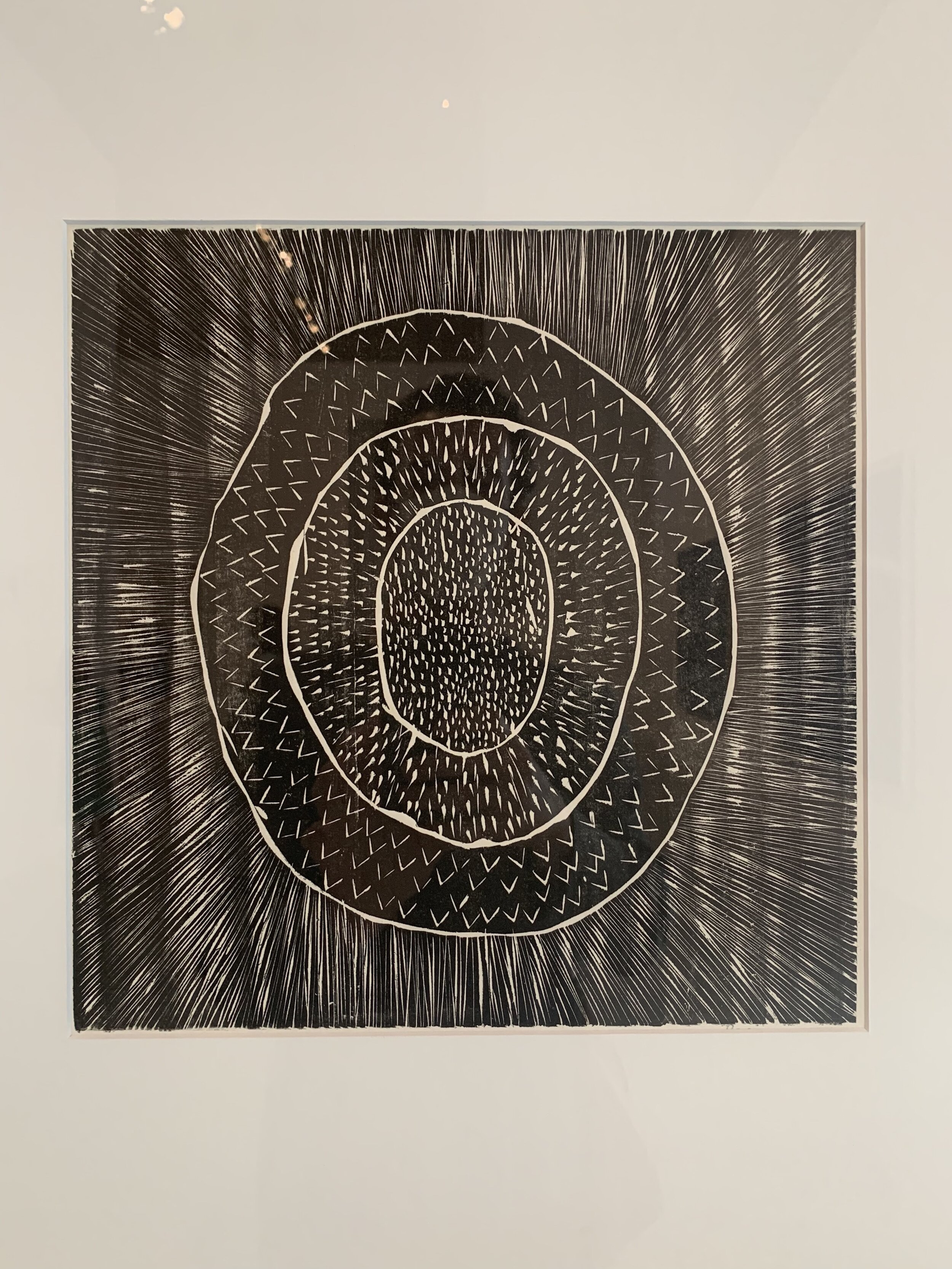

I get a publication called Palinopsia from an artist named Michaela Putz; photographs of the finger scuffed screens where images reside. There is an essay in a hidden fold of the book about a distant mediated love. Faint echoes in blurry constellations of light and other resonances.

Giacomo Alberico / Michaela Putz

The parakeet is very talkative. They had a companion, the photographer told me, who was quiet and one day just flew away. The symmetry of Lisbon to San Francisco is unnerving.

I look for rituals to orient myself. Outdoor markets and contemporary art venues. Conduit spaces for hungry vectors. ‘A smartphone is not a ‘thing’ in Arendt’s sense,’ says Han. It’s too clever and mutable. Things in this endlessly reconfiguring Airbnb are poor; too mutable to orient myself with.

The Gulbenkian gardens are magnificent in the golden light. In the birds and people lingering sense. People sitting peacefully in an amphitheater with two small children playing on the stage; healthy pond as mutable scenography.

Hospitality and habitability are assuming an infinitely detailed transactability that is covering everything in a rash of numbers; like sugar bumps on a child’s arm. It’s rowdy calls until early morning, a bloodcurdling scream, then quiet, then downpour.

Details from the Gulbenkian

Rituals like going to the river and swimming in fleeting eddies.

I don’t usually eat meat but the host has given me one of the three tables inside the small restaurant and so I feel obliged to take his recommendation for the steak that comes almost raw on a hot stone and cooks in front of me. The fado singer has a voice that feels like someone grabbing me by the collar and shaking me. The other fado singer was extremely genteel and well kempt. The two singers each did two songs and then went into the other room to look at their phones while the house played a Portuguese version of The Rhythm of the Night. It’s a been a day of mixed art and feelings.

The Boca Biennial brings me to the National Museum of Ancient Art to see a video by Anne Imhof of Eliza Douglas whipping a rising tide, lapping at their ankles. They stand on a submerged pier in a baroque 16th century female chapel of the Order of the Discalced Carmelites; a somber and passionate meditation on coevolving forms of worship. I have a satisfying sit with Bosch’s Temptation of Saint Anthony and in the garden outside.

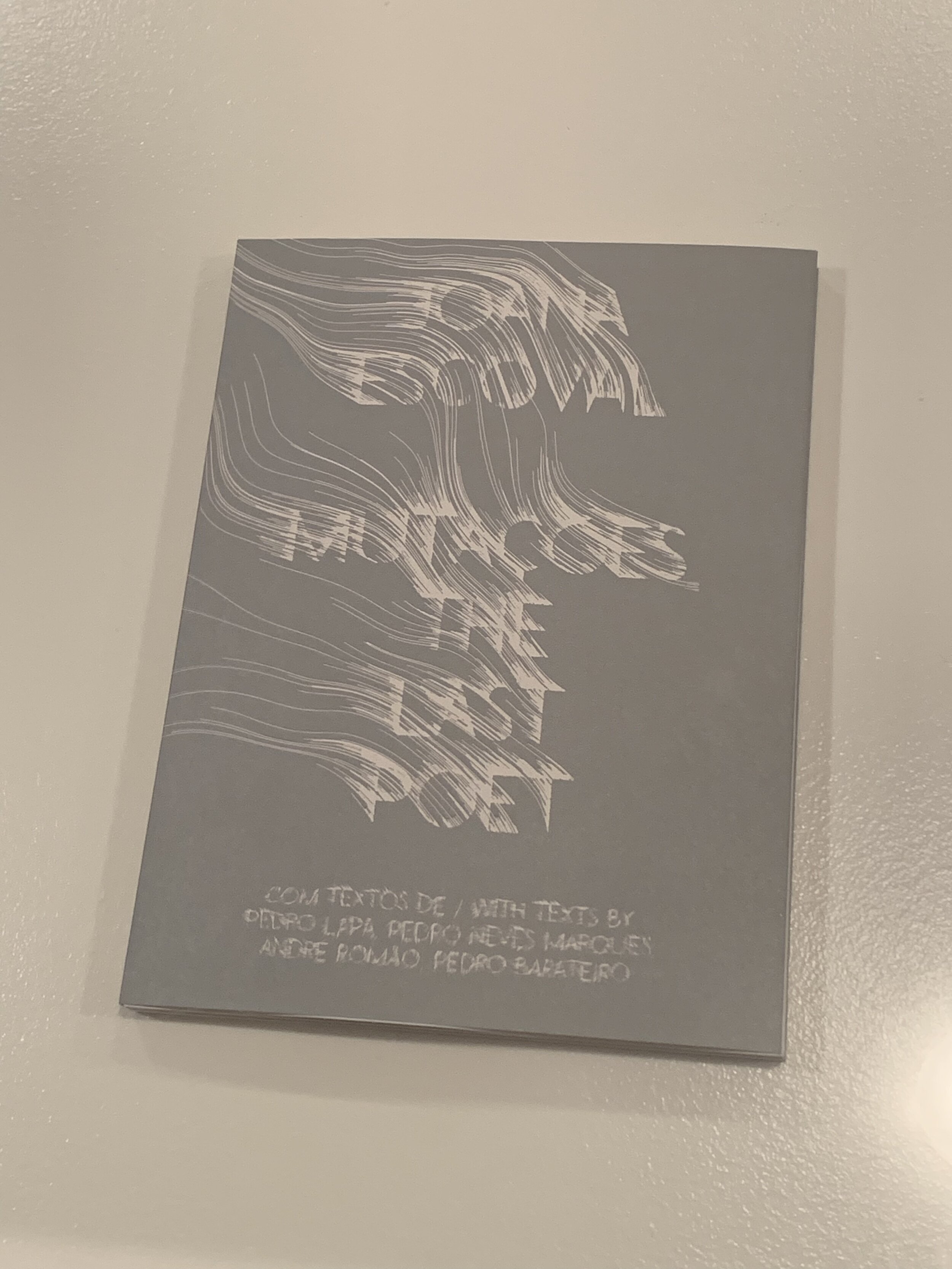

I attended a somber funerary performance by Grada Kilomba about the middle passage in front of the decommissioned power plant turned Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology. Afterwards I went to a commissioned Gus van Sant play about Andy Warhol, that despite the pleasures of listening to young accented Portuguese actors sing about Clement Greenberg, made me fall asleep. A text from a friend in the states alerted me to an exhibition of work from American artist Ellie Ga at the nearby Galeria Zé dos Bios. A room filled with their wondrous narrated light box performances resuscitating the evening from the Warholian abyss. Afterwards in the skillfully curated ZDB bookstore, a translator of Blanchot provided me a copy of a collection of critical essays on the implications of self-driving automobiles.

Details from the Berardo collection.

Some holes in a wall.

Sunday I wander around in the old town in the beautiful morning light. I read recently that the word religio had come from a careful consideration. Maybe it was Byung-Chul Han or maybe Bruno Latour? I can’t recall now. I took an hour or two to reread Good Entertainment and couldn’t seem to find it. Though I did track down a passage in the notes that helps rehabilitate myself from Western passion in art; ‘Wabi, a Japanese term for the experience of the beautiful, makes explicit reference to the unfinished, the transitory, or the fleeting. It designates as beautiful not the ripe cherry blossom, but the flowers at the moment of falling: “Were we to live on forever—were the dews of Adashino never to vanish, the smoke on Toribeyama never to fade away—then indeed would man not feel the pity of things. Truly the beauty of life is uncertainty.” Yoshido Kenko, Essays in Idleness.’ I had meant to note that for another essay, forthcoming here. Whatever connotative mutations these words might have undergone, I find myself at church in the world when I take meditative walks with a camera, open and noticing or carefully considering. This particular morning led me to a construction site. I wandered around inside for some time, taking in the views and sounds. The attunement to quotidian transcending.

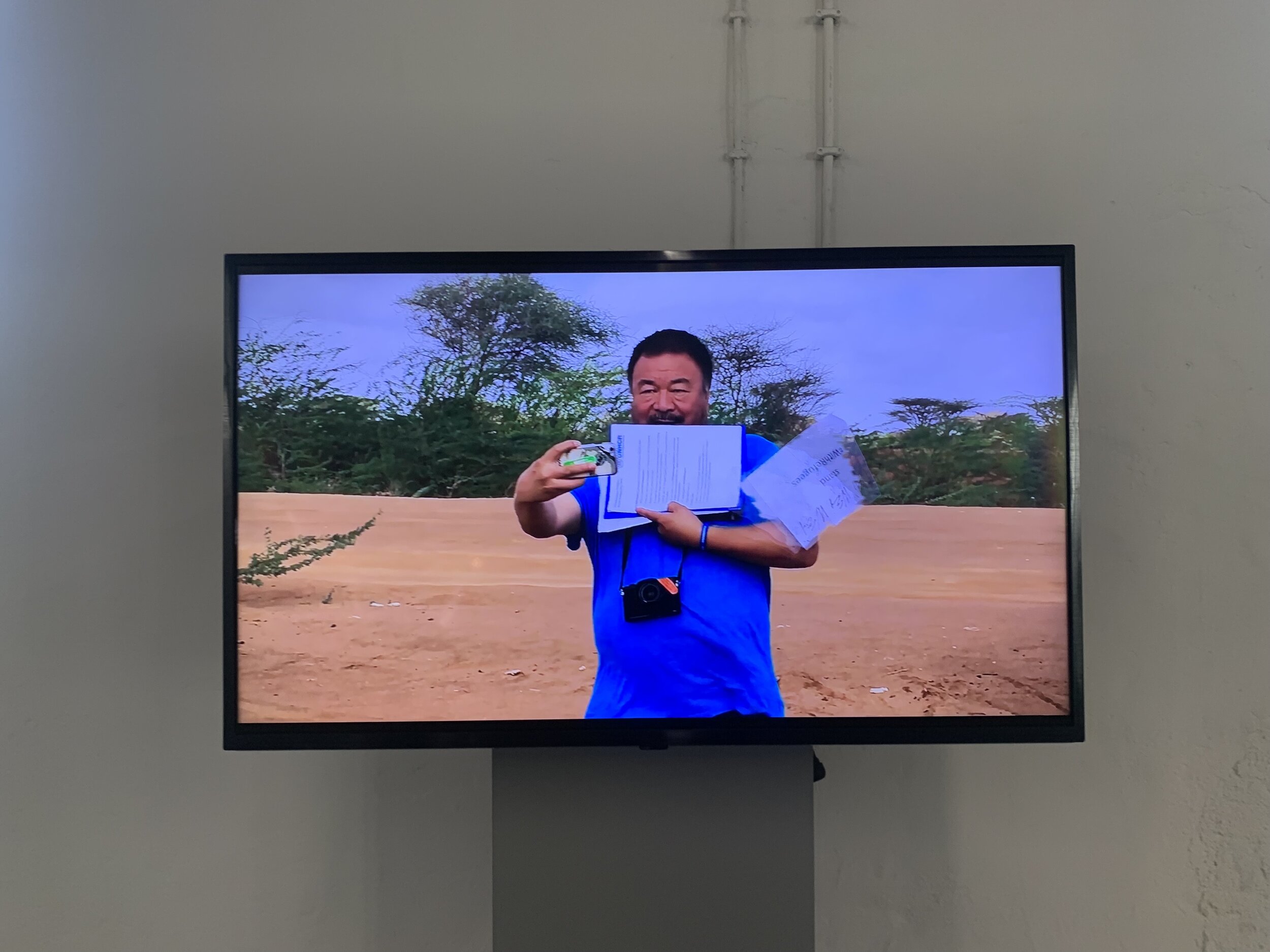

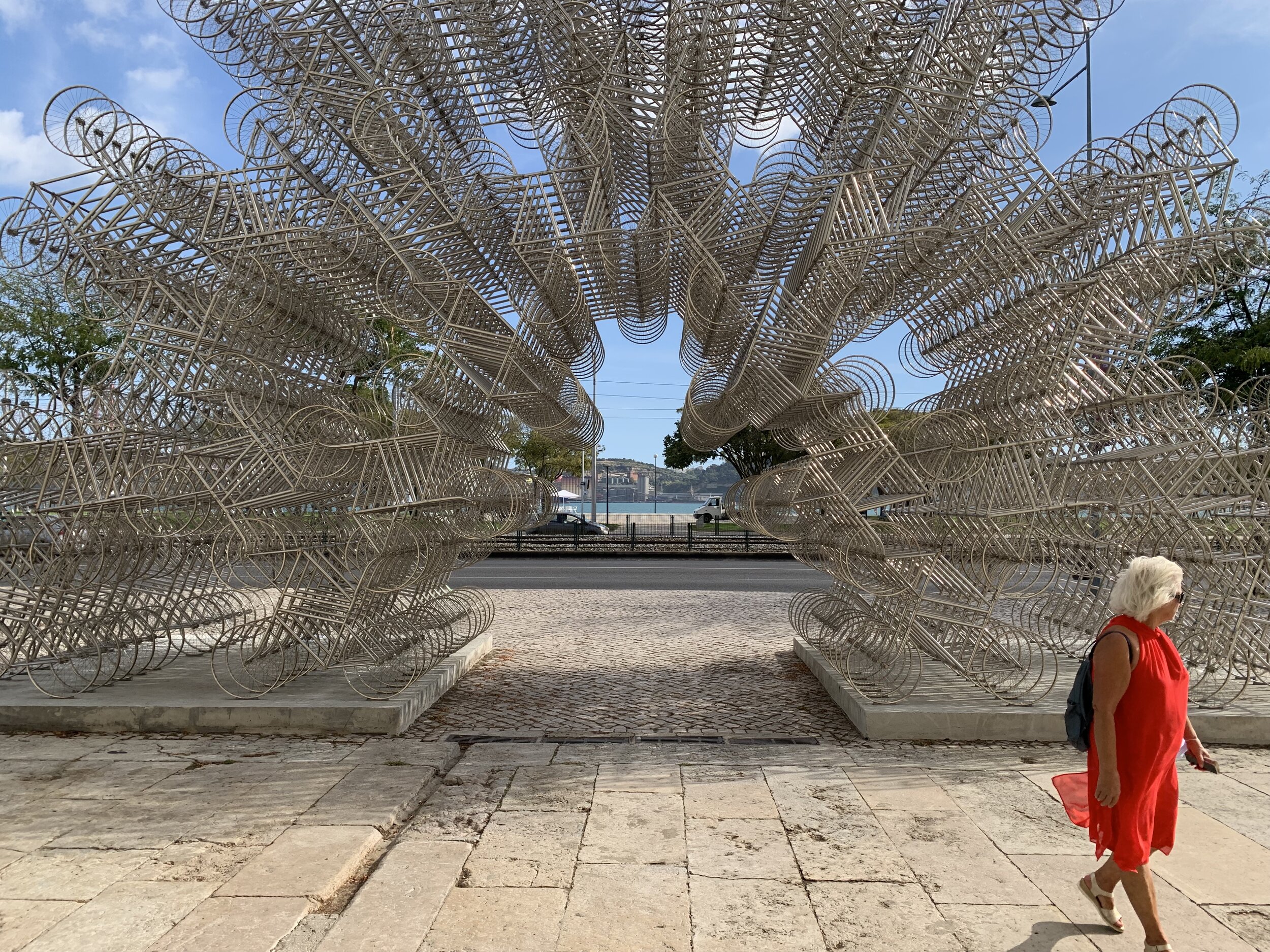

Monday, my last day, I went surfing with a group from the internet. Small fun waves and we got along well so we went for lunch afterwards. Fast friends from Mexico City and we connected over a mutual affection for Masala y Maiz (La Malinche). Jose recommended Ai Weiwei’s exhibition; Rapture.

My first impression was like walking into a cathedral. The cavernous space bullying, and the show—not unlike a sermon—indicting the viewer for the crimes of humanity. The volume compounding and consolidating into an undifferentiated mass of generalized guilt and perennial-seeming suffering. Proxy Ais as slovenly trickster messiahs. I watch one of the dozens of films for a few minutes that shows the artist playing with a patron in a the kind of temporary barracks you might see in a field hospital or refugee camp. For the biennial he was invited to participate in, he’s arranged visas and austere accommodations for mostly poor Chinese workers to attend the art event.

I’m aware all these issues are urgent and consequential and I know a little bit about most of them because I’m alive in the world today—though I’m not sure what to do with this scale of their representation. It also feels like being critical about the aesthetics of someone whose committed much of their life to raising awareness about social injustice feels—I don’t know… beside the point? Though there’s something here that troubles me, and obviously more than the mass of human suffering rendered by the artist and described by the didactics. It’s as though this work commands the viewer to be awestruck and seductively devastated while rendering them helplessly overwhelmed. Something vital seems subsumed, diffused and diluted by the circulation of this volume of visual representation; prayer-like thoughts, social media, the soar of righteous emotion and swirling pixels.

A person pauses beside me as we consider a stack of porcelain vessels depicting scenes of suffering refugees, and says almost to themselves ‘isn’t it lovely?’

No.

It is most certainly not. And I suspect the reason for so much suffering, has little to do with a lack of awareness or visual representation of these issues.

I heard a recent interview with an author I haven’t read, named Sheila Heti, on a podcast called Momus. She was saying that someone who loves a piece of work is probably more right about it than someone who doesn’t. And continued on that a work is not meant for—or speaking to—everyone. While I find questionable the idea of a ‘right’ or fixed position, I appreciate the general sentiment. It invites dialogue and thickens meaning, while de-privileging the recipient-participant-constituent of the work. I wonder how this piece might be experienced by a refugee living in Europe or how my daughter might experience it. I walk past a couple hundred feet of framed photographs of Ai’s middle finger pointing at monuments and another couple hundred feet of hundreds of thousands of legos assembled to represent the animals of the Chinese zodiac. I suppose the standard critique of spectacularized exhibition-making is tired and predicable. I suppose the critique of artist as messiah is tired and predicable. Maybe I’m tired and predictable. The numbing thrum of so many Raptures®; the staggering visibility of recursive suffering.

Addendum

Touch of grace general store

Young girl dancing by the bus stop

moving gracefully in staccato

like dodging unrelenting

tiny invisible assaults