Dear Paul,

I’m writing to you from in between the two volumes of your Technologies and Romance, on one of those partially cloudy mornings where the room glows and calms in suggestive succession and relational phasing. I wonder about our predilection for these kinds of dualisms, that the interesting writers and thinkers (and talkers and artists) usually set about shifting and collapsing, complicating and contaminating. In my feral education, I’ve come to situate the origin of this impasse, at the threshold of our media studies, to Heraclitus and Pythagoras, though I imagine it goes back much, much longer.

It has been a pleasure to sit with your thoughts. And move with them. On buses, in the foyer of the cinema, with friends I meet in line before the evening's performance at Oto. As much as your work, I was struck by your disposition. Tabling at the artist self publishers book fair with your life partner (and editor) and what appeared to me as a distillation of a lifetime of thinking and sharing. Your kind openness, presence, and sincere invitation to discuss these themes further. London, perhaps more than any other place I’ve lived, seems so rushed, constantly preoccupied. Your calm, thoughtful, spacious presence was truly a reprieve. Perhaps we found, or made, something like what the Greeks called kairos.

It was a special congregation in that curious humanist space, Conway Hall, the former headquarters of the Ethical Society. So many blending times and means of apprehension. I love the young booksellers from Peckham with their constellation of zines and the artists who offer themselves and their consuming explorations to the would-be receivers. One of my favorite characters in this clamorous scene, is the wise and kind convener of a long-running and beloved seminar who carves a softer space to pass down the common heirlooms they’ve cared for reveling in the insights and wonders of their interlocutors.

I’m a fan of what we could call memoir-laced intertextual philosophy, or what some recently have started calling auto-theory or perhaps what we might infer to be the constitution of writing itself, this particular twilight blend of romance and technology. My favorite parts in your book are the affections you share for your family and the epiphanal moments you return to. The magic of the music in a Norfolk jukebox. The county fair on a former wasteland where your inquisitive spirit lead you to peer behind the veil, in the intoxicating haze of candy floss and diesel-generators, at the ‘dark forces that made possible the fairground’s fervid fantasy and froth.’

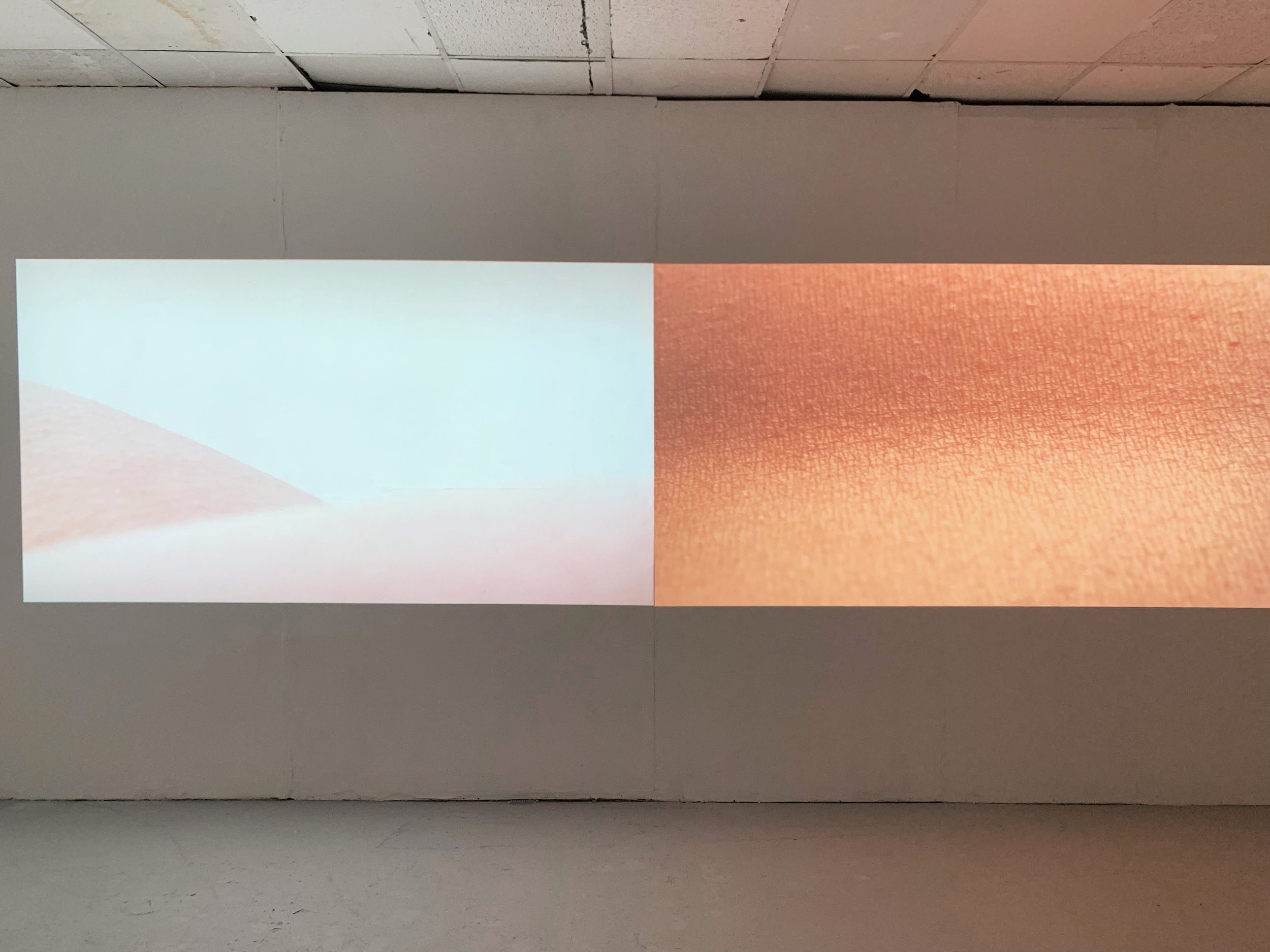

I love the Candle Time chapter, your enigmatic encounter with a camera technician filming a burning candle at art school, and the wondrous Richter paintings of a candle and his daughter Betty. It brings to mind Prachaya Phintong’s A proposal to set CH4*5.75H20 on fire (work in progress) comprised of a 16mm film projector projecting a flickering image of an alternative energy. And also 8’22” and 17’36” in my Heritage and Debt / The June of Everything. We could call this charnel grounds or diminishingly yours… and an errant saxophone mixing with ocean.

I love your Frankfurt-style reading of Kumiko, the Treasure Hunter that surprisingly ends in a defense of magic realism, towards the capacity for one to try to inscribe meaning to their own lives, socially, outside of the increasingly carceral logics of economic and scientistic determinism. I feel a bit like Kumiko, going to a post-Brexit London for a masters degree in Art at a striking Goldsmiths to see if I can find a way out the bleak horizon of precarity in a US hemorrhaging from pandemics and the Trump presidency, while I collect books for my non existent library on a waning visa. It’s not the first time I’ve embarked on this quixotic (Kumikian?) kind of dérive. I did it before when I took a trip to Mexico to learn what La Maliche might be, with a $1000 left in my bank account, after reading a Berardi essay. Is this the perennial romantic spirit? It’s not looking good, but it has to be better than this...

I began writing you this letter from the ICA where I went to see two films. One about police cameras and another about a married volcanologist couple who died pursuing their vocation. I often will try to balance out films I feel obliged to watch and those that revel in more romantic registers. Of course these categories are always partial and porous, as both these films can attest.

I have to confess, somewhat embarrassingly, I searched that insidious platform whose name I won’t write, ‘romantic poetry cloud loneliness’ to find the provenance of that ‘…most famous line of English romantic poetry compar[ing] human loneliness with a condition of a cloud.’ What an interesting anticipation...

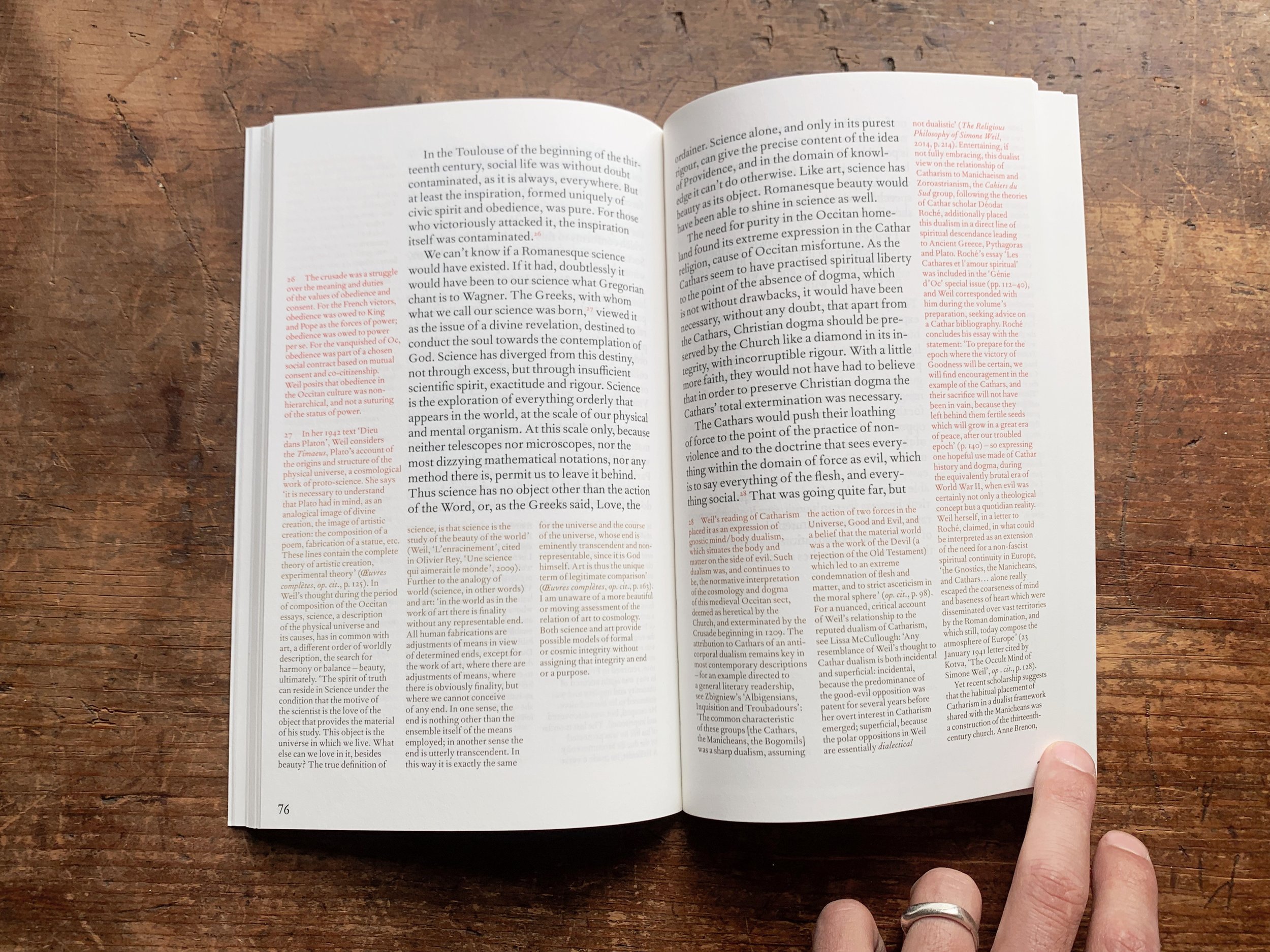

I also wanted to note, and amplify, your working definition of romanticism (page 100 of Technologies and Romance).

The early modern arts, and the aesthetics of Romanticism may generally be considered a response to, and a refusal of increasing and encroaching technological hubris. Romanticism is a willingness and perhaps a need, to maintain a certain modesty, empathy, humility, mystery and fragile sensitivity, to balance an increasingly robust, technologised and unnatural epoch marked out by an all-too-human and yet also all-too-inhumane industrial revolution, a revolution which is, in its turn, accompanied by the growing confidence and ascendancy of rational, scientific thought in modern society.

I love the Deleuze and DeLanda inspired suggestion that we might be more ‘...a sky-like mass of volatile becomings, non-organized, swirling, baroque in their complexity and behaviors, eventful and intensive as opposed to existential and extensive.’ And Deleuze himself, ‘we wonder about what makes the individuality of an event: a life, a season, a wind, a battle, 5’ o’clock.’

To which I’m compelled to add the questions, Who is going to remember the hard-won lessons? ‘Who is going to pick up the cast aside treasures? Who is going to repeat the important things passed down? Who is going to thank the farmer and baker and share their gifts? Who is going to respond to all the wonderful works of art? Who is going to question the given truths that cause so much suffering? Who is going to share the language that names the many forms of oppression? Who is going to practice living otherwise?

I wanted to linger a little on your New Media Heir to Romanticism chapter, with the intertextual dialogue with Benjamin and Steyerl. You offer:

The artist is left behind by image and by language. Now we are merely vehicles, automatons, serving, delivering images and language on their behalf.

The first part of this is, for me, a sad truth, even from myself, and the other part is where I’d like to elaborate a little. I’ve been moving through this feeling of serving a cruel and instrumental technology—or perhaps what Howard Caygill means when he asks ‘if we were not just a by-product but a romance of technology, a toy contrived to amuse and comfort itself during its slow gestation?’ and I’ve begun to wonder if the hundreds of thousands of images and recordings I save, share and submit to surveillance, are a form of mutual learning about quotidian beauty and the ineffable with our non-dual cyborg becoming. Of course this poetic conceit doesn’t stand in the way of explicitly demanding and building non-coercive, non-exploitative technologies, or more affirmatively put, cooperative non-profit tools for mutual benefit and enjoyment. Technologies of romance…

Kind thanks,

Perry